El oficio de la arqueología

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.24901/rehs.v37i148.215Palabras clave:

arqueología artesanal, Movimiento de Artes y Oficios, práctica política y alienaciónResumen

La idea de la arqueología como arte desafía la separación entre razonamiento y ejecución, teoría y práctica, que hoy caracteriza a la disciplina. El Movimiento de Artes y Oficios de fines del siglo XIX estableció a la artesanía como una manifestación estética de oposición. Asentamos a la artesanía dentro de una crítica marxista del trabajo alienado y proponemos una práctica unificada de mano, corazón y mente. Los debates engendrados por la arqueología postprocesual han definido firmemente a la arqueología del presente como una práctica cultural y política. Sin embargo, muchos arqueólogos aún no saben cómo implementar estas ideas. Argüimos que una solución a este dilema consiste en pensar en la arqueología como artesanía. Esta resolución no provee un método o un libro de recetas para la práctica de la arqueología, puesto que el núcleo de nuestro argumento es que la intención de regularizar la arqueología constituye precisamente la causa de alienación de la disciplina. Por el contrario, deseamos considerar a la arqueología como un modo de producción cultural, una práctica unificada que involucra al pasado, al arqueólogo, al público, al cliente y a la sociedad contemporánea.Citas

BARKER, F. y J. D. HILL. “Archaeology and the Heritage Industry”. Archaeological Review From Cambridge, 7(2) (1988).

BELL, D. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. Londres: Heineman, 1974.

BINTLIFF, J. “Why Indiana Jones is Smarter than the Postprocessualists”, Norwegian Archaeological Review, 26 (1993): 91-100.

BLOOM, A. The Closing of the American Mind. Nueva York: Simon and Schuster, 1987.

BRAVERMAN, H. Labor and Monopoly Capital: the Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. Londres: Monthly Review Press, 1974.

CHIPPINDALE, C. “Stoned Henge: Events and Issues at the Summer Solstice, 1985”. World Archaeology, 18(1) (1986): 38-58.

CHIPPINDALE, C., C. P. DEVEREUX, P. FOWLER, R. JONES y T. SEBASTIAN. Who Owes Stonehenge? Londres: Batsford, 1990.

COLLCUTT, S. “The Archaeologist as Consultant”. En Archaeological Resource Management in the UK: An Introduction, eds., J. Hunter e I. Ralston, 158-168. Dover: Alan Sutton, 1993.

CUNLIFFE, B. The Report of a Joint Working Party of the Council for British Archeology and the Department of the Environment. Londres: Department of the Environment and Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1990.

_____. “Publishing in the City”. Antiquity, 64 (1982): 667-671.

CUNNINGHAM, R. D. “Why and How to Improve Archaeology's Business Work”. American Antiquity, 44 (1979): 572-574.

DECCICO, G. “A Public Relations Primer”. American Antiquity, 53 (1988): 840-856.

DEETZ, J. D. In Small Things Forgotten, Garden City, Nueva York: Anchor Press, 1977.

DORMER, P. “The ideal World of Vermeer’s Little Lacemaker”. En Design After Modernism, ed. J, Thackara, 135-144. Londres: Thames and Hudson, 1988.

_____. The Meanings of Modern Design. Londres: Thames and Hudson, 1990.

_____. The Art of the Maker: Skill and its Meaning in Art, Craft and Design. Londres: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

DUKE, P. “Cultural Resource Management and the Professional Archaeologist”. SAA Bulletin 9(4) (1991): 10-11.

ENGLISH HERITAGE. The Management of Archaeology Project, 2a ed. Londres: Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission and Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1991.

FITTING, J. E. “Client Orientated Archaeology: A Comment on Kinsey’s Dilemma”. Pennsylvania Archaeologist, 48 (1978): 12-25.

FLANNERY, K. V. “The Golden Marshalltown: A Parable for the Archaeology of the 1980s”. American Anthropologist, 84 (1982): 265-279.

FULLER, P. “The Proper Work of the Potter”. En Images of God: Consolations of Lost Illusions. Londres: Hogarth, 1990.

GATHERCOLE, P. y D. LOWENTHAL. The Politics of the Past. Londres: Unwin Hyman, 1989.

GERO, J. “Socio-Politics of Archaeology and the Women-at-Home, Ideology”. American Antiquity, 50 (1985): 342-350.

_____. “Gender Divisions of Labor in the Construction of Archaeological Knowledge in the United States”. En Archaeology of Gender, eds. N. Willo y D. Walde, 96-102. Calgary: University of Calgary, 1991.

GIAMATTI, B. A Free and Ordered Space: The Real World of the University. Nueva York: W. W. Norton, 1988.

GRINT, K. The Sociology of Work: An Introduction. Cambridge: Blackwell Polity, 1991.

HARAWAY, D. Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. Londres: Routledge, 1989.

HARDING, S. The Science Question in Feminism. Londres: Open University Press, 1986.

HARVEY, D. The Condition of Postmodernity. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

HILLS, C. “The Dissemination of Information”. En Archaeological Resource Management in the UK: An Introduction , eds. J. Hunter e I. Ralston, 215-224. Dover: Alan Sutton, 1993.

HODDER, I. “Writing Archaeology: Site Reports in Context”. Antiquity , 62 (1989): 268-274.

HOODER, I., M. SHANKS, A. ALEXANDRI, V. BUCHLI, J. CARMAN, J. LAST y G. LUCAS. Interpreting Archaeology: Finding Meaning in the Past. Londres: Routledge, 1995.

HOUNSHELL, D. A. From the American System to Mass Production 1800-1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

HUNTER, J. e I., RALSTON, eds. Archaeological Resource Management in the UK: An Introduction . Dover: Alan Sutton, 1993.

INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORANY ARTS. William Morris Today. Londres: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1984.

INSTITUTE OF FIELD ARCHAEOLOGISTS. By-Laws of the Institute of Field Archaeologists: Code of Conduct. Birmingham: Institute of Field Archaeologists, 1988.

_____. By-Laws of the Institute of Field Archaeologists: Code of Approved Practice for the Regulation of Contractual Arrangements in Field Archaeology. Birmingham: Institute of Field Archaeologists, 1990.

JOUKOUSKY, M. A Complete Manual of Archaeology. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1980.

KERR, C. The Uses of the University. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964.

KNORR-CETINA K. D. The Manufacture of Knowledge. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1981.

KNORR-CETINA, K. D. y M. MULKAY, eds. Science Observed: Perspectives on the Social Study of Science. Londres: Sage, 1983.

KNUDSON, R. A. “North America's Threatened Heritage”. Archaeology, 42 (1989): 71-73, 106.

LATOUR, B. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society. Londres: Open University Press, 1987.

LATOUR, B. y S. WOOLGAR. Laboratory Life. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1979.

LAYTON, R.,ed. Conflict in the Archaeology of Living Tradition . Londres: Unwin Hyman, 1989a.

_____. Who Needs the Past? Indigenous Values in Archaeology. Londres: Unwin Hyman, 1989b.

LEONE, M. P., P. B. POTTER Jr. y P.A. SHACKEL. “Toward a Critical Archaeology” Current Anthropology. 28 (1987): 283-302.

LYNCH, M. Art and Artifact in Laboratory Science: A Study of' Shop Work and Shop Talk in a Research Laboratory. Londres: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985.

LYNTON, E. A. y S.E. ELMAN. New Priorities for the University. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1987.

MCBRYDE, I., ed. Who Owns the Past? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

MCGIMSEY, C. R. III y H. A. DAVIS, eds. The Management of Archaeological Resources: The Airlie House Report. Special Publication. Washington: Society for American Archaeology, 1977.

MCGUIRE, R. H. “Archaeology and the First Americans”, American Anthropologist, 94 (1992): 816-836.

NOBLE, D. Forces of Production: a Social History of Industrial Automation. Nueva York: Knopf, 1984.

OLLMAN, B. Alienation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

PAYNTER, R. “Field or Factory? Concerning the Degradation of Archaeological Labor”. En The Socio-Politics of Archaeology, J. M. Gero, D.M. Lacy y M. L. Blakey, 17-30. Amherst: Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, 1983.

PICKERING, A., ed. Science as Practice and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press , 1992.

POTTER, P. B. "The “What” and “Why” of Public Relations for Archaeology: A Post script to DeCicco's Public, Relations Primer". American Antiquity, 55 (1990): 608-613.

PREUCEL, R., ed. Processual and Postprocessual Archaeologies: Multiple Ways of Knowing the Past. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations, Southern Illinois University, 1991.

RAAB, M. L., T. KLINGER, M. B. SCHIFFER y A. GOODYEAR. “Clients, Contracts, and Profits: Conflicts in Public Archaeology”. American Anthropologist, 82 (1980): 539-551.

REDMAN, C. L. “In Defense of the Seventies”. American Anthropologist, 93 (1991): 295-307.

ROSE, M. A. The Post-Modern and Post-Industrial: A Critical Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

ROSOVSKY, H. The University: An Owner’s Manual. Nueva York: W. W. Norton, 1990.

SCHULDENREIN, J. “Cultural Resource Management and Academic Responsibility in Archaeology : A Rejoinder to Duke”. SAA Bulletin, 10(5) (1992): 3.

SHANKS, M. Experiencing the Past: On the Character of Archaeology. Londres: Routledge, 1992.

_____. Classical Archaeology: Experiences of the Discipline. London: Routledge, 1995.

SHANKS, M. e I. HODDER. “Processual, Postprocessual and Interpretive Archaeologies”. En Interpreting Archaeology: Finding Meaning in the Past. I. Hodder, M. Shanks, A. Alexandri, V. Buchli, J. Carman, J.Last y G. Lucas, 3-29. Londres: Routledge, 1995.

SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON. Archaeological Publication, Archives, and Collections: Towards a National Policy. Londres: Society of Antiquaries, 1992.

SWAIN, H., ed. Competitive Tendering in Archaeology. Hertford: Rescue Publications/Standing Conference of Archaeological Unit Managers, 1991.

SYKES, C. J. ProfScam: Professors and the Demise of 'Higher Education. Washington: Regnery Gateway, 1988.

THOMAS, J. Time. Culture and Identity: An Interpretive Archaeology. Londres: Routledge, 1995.

THOMPSON, E. P. William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary. Londres: Merlin, 1977.

TILLEY, C. “On Modernity and Archaeological Discourse”. En Archaeology After Structuralism, eds. I. Bapty y T. Yates, 127-152. Londres: Routledge, 1990.

_____. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg, 1994.

TILLYARD, S. K. The Impact of Modernism 1900-1920: Early Modernism and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Edwardian England. Londres: Routledge, 1988.

TOURAINE, A. The Post-Industrial Society: Tomorrow´s Social History: Classes, Conflicts and Culture in the Programmed Society, trad. F. X. Leonard Mayhew. Londres: Random House, 1971.

UCKO, P. Academic Freedom and Apartheid: The Story of the World Archaeological Congress. Londres: Duckworth, 1987.

WALKA, J. J. “Management Methods and Opportunities in Archaeology”. American Antiquity, 44 (1979): 575-582.

WALSH, K. The Representation of the Past: Museums and Heritage in the Postmodern World. Londres: Routledge, 1992.

WELSH OFFICE. Planning Policy Guidance Note 16: Archaeology And Planning. Cardiff: Welsh Office, 1991.

WYLIE, A. “Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Feminist Critiques and Archaeological Challenges”. En Archaeology of Gender , eds. N. Willo y D. Walde, 17-23. Calgary: University of Calgary, 1991.

YOFFEE, N. y A. SHERRATT, eds. Archaeological Theory: Who Sets the Agenda? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Publicado

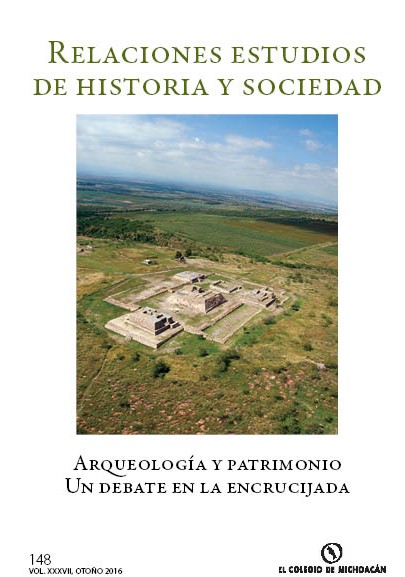

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derecho de los autoresDe acuerdo con la legislación vigente de Derechos de Autor, la revista Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad reconoce y respeta el derecho moral de los autores, así como la titularidad del derecho patrimonial, el cual será transferido –de forma no exclusiva– a la revista para permitir su difusión legal en Acceso Abierto.

Los autores pueden realizar otros acuerdos contractuales independientes y adicionales para la distribución no exclusiva de la versión del artículo publicado (por ejemplo, incluirlo en un repositorio institucional o darlo a conocer en otros medios en papel o electrónicos), siempre que se indique clara y explícitamente que el trabajo se publicó por primera vez en la revista Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad.

Para todo lo anterior, los autores deben remitir la carta de transmisión de derechos patrimoniales de la primera publicación, debidamente requisitada y firmado. Este formato debe ser remitido en PDF a través de la plataforma OJS.

Derechos de los lectores

Bajo los principios de Acceso Abierto los lectores la revista tienen derecho a la libre lectura, impresión y distribución de los contenidos de la revista por cualquier medio, de manera inmediata a su publicación en línea. El único requisito para esto es que siempre se indique clara y explícitamente que el trabajo se publicó por primera vez en la revista Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad y se cite de manera correcta la fuente y el DOI correspondiente.